Long-term liabilities at the University of Leicester

Published: 2nd April, 2021

We have claimed that the University of Leicester is ‘on the verge of bankruptcy’. This claim is based on our reading of the 2019/20 financial statements, that were published (several weeks later than usual) in early March, and on other publicly-available financial information, e.g. University executives’ decision to increase short-term borrowing from the Bank of England under the Covid Corporate Financing Facility. Our employer is one of only three universities to avail itself of this facility; it’s one of only two universities which still owes money to the Bank of England; it owes a total of £60m, all of which must be repaid within 12 months.

Of course, we’d love to have access to more detailed financial information, but the University’s executive has repeatedly declined to share with us such information. But late last year – not long after the president and vice-chancellor first announced ‘Shaping for Excellence’ – some of our members started digging into the accounts from previous years and those minutes of University Council that are published. The resulting report, completed in January, makes shocking reading. The full report is attached. A summary is below.

In the light of recent news of (a) the University of Leicester executive board’s ‘Shaping for Excellence’ plan , that we’re told will involve compulsory redundancies, and (b) ‘problems’ that appear effectively to be breaching of financial covenants with three of the University’s five creditors , we examine our employer’s ‘long-term strategy’ and situate it in the context of financial performance and decision-making over the past few years. Our principal findings are as follows. Some necessarily involve a degree of conjecture given that much key information is private.

- In 2016/17, the University effectively breached loan covenants with Barclays and the European Investment Bank. Leaders’ response was to move to increase indebtedness by two-thirds, taking on an additional £55m of debt with two US insurance funds, Lincoln National Life and Pacific Life.

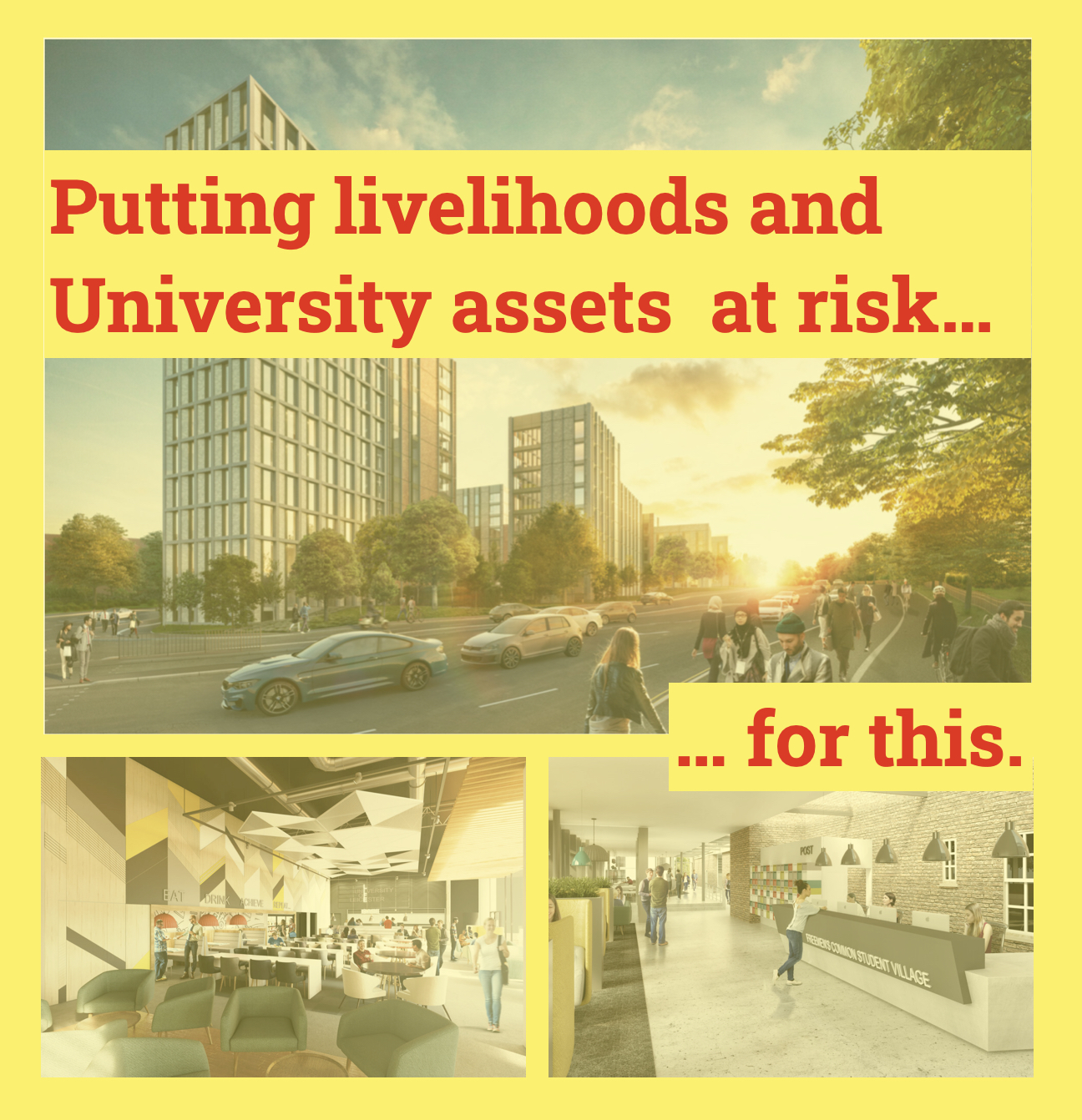

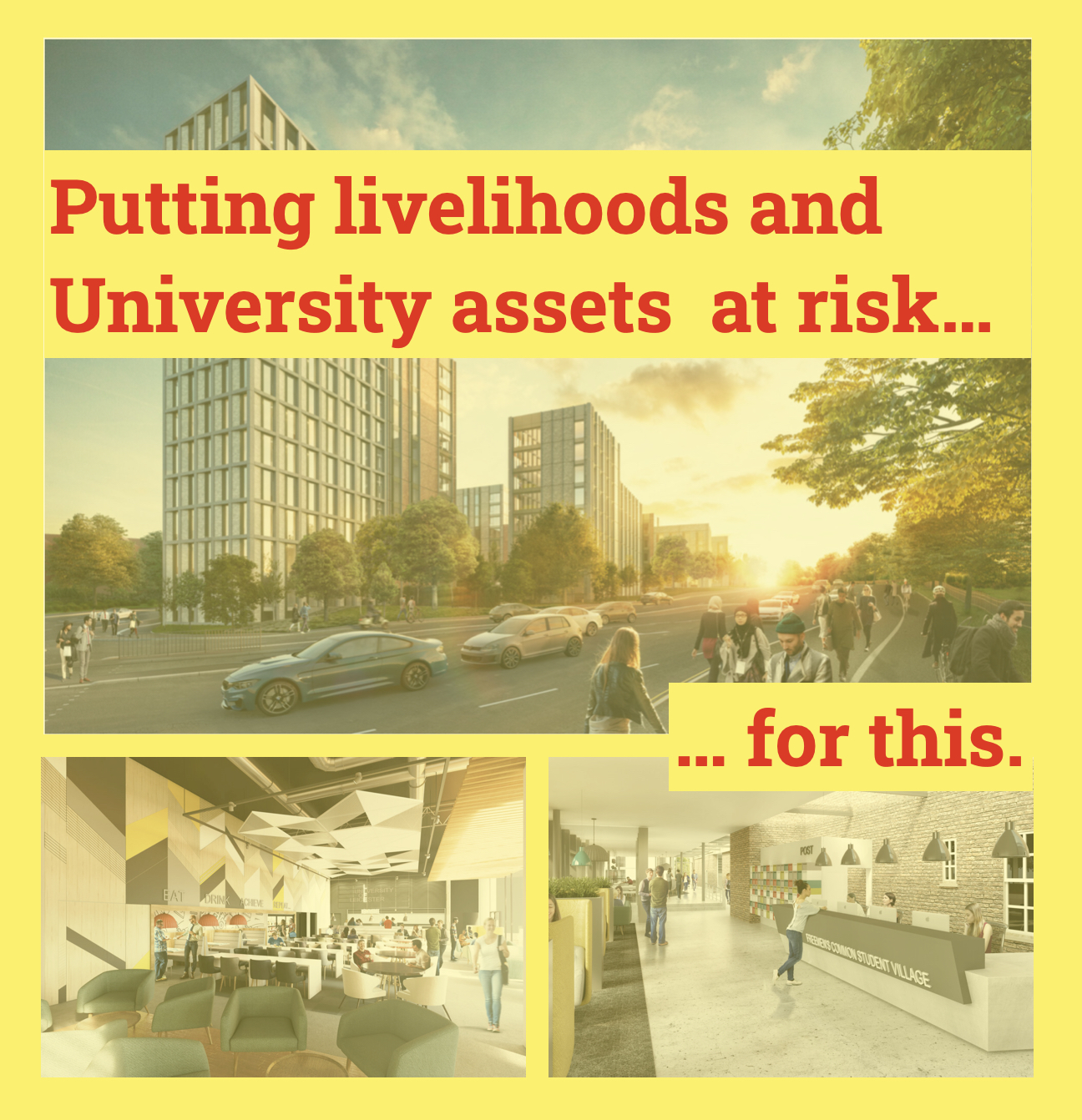

- In 2018/19, decision-makers agreed to the creation of a ‘special purpose vehicle’ – Freemens Common Village LLP – leveraging some of this new debt to take on further long-term liabilities of £124m. Because of the financial engineering involved (‘securitisation’) this £124m is ‘off balance sheet’. This £124m funds new student accommodation, teaching facilities and a carpark on the site. The underlying investment is rated as risky (BBB– according to ratings agency S&P); yet the bonds held by investors have a rating of AA. Such a de-risking (from the perspective of investors) can only be achieved, we hypothesise, by transferring equivalent risk to the University and its stakeholders. A consequence of this transaction is that investors may have indirect rights to intervene in the setting of future rents and service charges and that the University will guarantee certain minimum occupancy levels. It may even be possible that, in the event of default, the University would forfeit the control of the Freemen’s Common site to investors.

- Including the off-balance sheet Freemen’s Common project, the University’s long-term financial liabilities now total almost one-quarter of a billion pounds. f

- In 2017, Council ‘confirmed … its willingness to accept and encourage an increased degree of risk in pursuit of the University’s mission and objectives’. However we’re unaware of students, staff and other stakeholders being informed of this new, more risk-loving, approach to our activities; still less can we find trace of them being consulted as to their views on its appropriateness.

- In 2020, the University again stands in what appears to be effective breach of covenants, this time with three of its five lenders. We do not know which creditors, nor the terms of the covenants, but it is possible one or more of these creditors now has the right to demand a role in the governance of the University.

- We raise questions about the roles played in the above by three key decision-makers, viz., the current Deputy Vice-Chancellor, the current Chief Operating Officer and the current Chair of Council; and in the light of this we thus also have concerns regarding the appropriateness of the University’s governance structures and the ways in which responsibilities have been enacted within them.